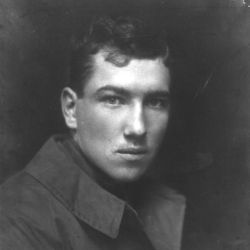

Robert Graves

Robert Von Ranke Graves was born in Wimbledon on 24th July 1895, the third of five children born to Alfred Perceval Graves and his second wife, Amalie Elizabeth Von Ranke. Graves was educated at Charterhouse School, where he was befriended and influenced by one of the masters, mountaineer, George Mallory. In 1914, Graves has just won a scholarship to St John’s College, Oxford, when the First World War began, so he put his studies to one side and enlisted, being commissioned into the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Although not a popular officer, Graves formed one important friendship early in the war, with fellow Fusilier, Siegfried Sassoon. He also wrote and published war poetry, the first volume of which was entitled Over the Brazier.

On July 20th 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, Graves was caught in shellfire and badly wounded in the chest and thigh. The battalion doctor, Captain J. C. Dunn, believed that nothing could be done to save Graves’ life, so he was left on a stretcher until the following day, when it was discovered that he was still alive. He was immediately transferred to hospital at Heilly, although the casualty list had already been prepared and a letter of condolence had been dispatched to his parents.

By the time this letter was received, Graves had arrived at Rouen, where he scribbled a hasty note to his parents. Upon receipt of this, the grief-stricken Graves family were thrown into confusion and it was not until 30th July that they received official confirmation that Robert was alive and would soon be arriving in England. In the meantime, however, The Times had printed Graves’ name among the casualties and were obliged to publish a retraction on August 5th.

Graves recovered fairly quickly from his wounds and was passed fit by a medical board on November 17th, returning to France in January 1917. However, the damage caused to his lungs was more serious than anticipated and he succumbed to pneumonia. He was sent to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight to recuperate.

In July 1917, Siegfried Sassoon made his Declaration against the continuation of the war and upon hearing of this, Graves travelled to London, where he met with Edward Marsh and Robbie Ross, both of whom were equally concerned for Sassoon’s future. Graves then travelled on to the regimental headquarters at Litherland, where he persuaded Sassoon that the authorities would never court-martial him, as Sassoon hoped, but would have him declared insane. Sassoon agreed to appear before a medical board, which pronounced him as suffering from neurosis and he was sent to Craiglockhart Military Hospital in Edinburgh.

January 1918 saw Graves’ marriage to Nancy Nicholson, with their first child Jenny being born a year later. In October 1919, Graves resumed his education at Oxford, although he would be forced to postpone this as financial and health problems beset him. Nancy gave birth of a second child, David, in March 1920, followed by a daughter, Catherine two years later and finally Sam in January 1924. As the family grew, so did the financial problems and Graves, now studying again, borrowed money from family and friends, including Sassoon.

Graves finally completed his degree in 1925 and accepted the post of English Professor at Cairo University, so the whole family embarked for Egypt, together with the American poet Laura Riding, with whom Graves was collaborating on several projects. However, the position in Cairo proved disappointing and within six months they had all returned to Oxfordshire, where Graves and Laura Riding became lovers.

By September 1929, Graves had finished his autobiography Goodbye To All That, whereupon he and Laura moved to Majorca, leaving many sad and angry friends and relations behind, upset by both their lifestyle and the content of Graves’ book. Both Edward Marsh and Siegfried Sassoon took action against Graves’ publishers, forcing changes to be made prior to publication.

In Majorca, Graves began working on his historical novel, I Claudius, while Laura, who believed herself to be a Goddess, manipulated the emotions of everyone around her. In 1936, the Spanish Civil War forced the couple to abandon Majorca and they settled in Northern France with an old friend, Alan Hodge and his new wife Beryl. The outbreak of the Second World War saw all four of them heading for America, where Laura began an affair with critic Schuyler Jackson. Graves returned to England, followed by Beryl Hodge, who had become very attached to him. While Alan Hodge agreed to an amicable divorce, Nancy would not relent, so Graves and Beryl moved in together and their son, William was born in September 1940.

Graves’ children from his first marriage all served in the armed forces during the Second World War, except for Sam, who was exempted on account of his deafness. Jenny and Catherine enlisted in the WAAF’s while David served, like his father, with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, fighting in Burma, where he was shot and killed in April 1943.

Beryl had two more children during the war: Lucia in 1943 and Juan in 1944, then after the conflict was over, the family moved back to Majorca. In 1949, Nancy finally agreed to a divorce, enabling Graves and Beryl to marry in May 1950.

Over the remaining years of his life, Graves had relationships with several “muses”, some more serious than others. In January 1953, Beryl gave birth to her final child, Tomas, and remained loyal to Graves, despite his behaviour with other women and the divisions this caused in their marriage.

In 1961, Graves was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, which position he held until 1966, when he stepped down and was replaced by Edmund Blunden. 1964 brought tragedy, when Graves’ oldest child, Jenny died suddenly, although Graves did not attend her funeral.

By the early 1970s, Graves’ memory and eyesight were beginning to fail and over the next fifteen years, despite Beryl’s loyal and unwavering care, his health slowly deteriorated until his death on December 7th 1985, at the age of 90.