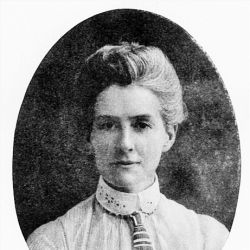

Edith Cavell

The very name of this nurse and patriot came to represent all that was good about the British during the First World War, while also showing the public the very worst side of humanity.

Born on 4th December 1865 at Swardeston in Norfolk, Edith Cavell was the daughter of the parish priest, Frederick and his wife, Louisa. Edith was the oldest of four children and they grew up together in the vicarage where they lived a poor but contented life. Throughout her childhood, Edith maintained a talent for painting and also enjoyed ice skating in the winter, tennis in the summer and dancing all year round. She was mainly educated at home, but later attended Laurel Court in Peterborough, where she showed a talent for French. This resulted in a position as governess for a family in Brussels, where Edith remained for five years. In 1895, she returned to Norfolk briefly, before taking a position as a trainee nurse at the London Hospital. She carried out a variety of roles including as a private nurse and Night Superintendent at a London Hospital for the homeless.

By 1906, Edith was Matron at one of the Queen’s District Nursing Homes, and by the following year she was back in Brussels, in charge of a training school for nurses on the outskirts of the city. Edith often returned to Norfolk to visit her mother and it was while staying in Norwich that she heard of the declaration of war. Despite pleas from her family to remain in England, Edith knew that her place was with the wounded in Belgium, so she returned there on August 3rd 1914, one day before Great Britain even became involved in the conflict.

Her clinic in Brussels was made into a Red Cross hospital and she worked there with more than sixty British nurses until Brussels was captured by the advancing Germans. Although the nurses were all sent home, Edith and her assistant, Miss Wilkins, remained. As the Allies retreated, many French and British soldiers became isolated from their units and those that found their way to Edith’s hospital were secure. A lifeline was set up by the Prince and Princess de Croy and Edith played an integral part in helping more than 200 Allied soldiers reach the safety of neutral Holland, over the ensuing months. Edith knew the risks involved in helping the men and took great pains not to involve anyone else at the hospital in the scheme.

In working for the Red Cross, which afforded Edith a degree of protection, she should have remained detached, but her humanitarian personality meant that she found it impossible not to help these stranded men. However, in July 1915, two members of the lifeline were arrested and within five days, the Germans also took Edith into captivity, telling her that the other prisoners had confessed everything. Believing there to be no hope of concealment, Edith told her captors all that they wanted to know. At the trial which followed, Edith openly admitted her guilt and was condemned to death. The American and Spanish embassies tried to intervene, but to no avail and Edith Cavell was shot by firing squad on October 12th.

There was international condemnation of this act and the British government wasted no time in using Edith’s death for propaganda purposes, causing recruitment numbers to double in the following two months. After the war a ceremony was held at Westminster Abbey and her body was re-interred at Norwich Cathedral.

None of this aftermath would really have suited Edith, who saw herself as merely doing her duty. On the eve of her execution, she summed up her own feelings towards her situation, in the full knowledge and acceptance of what lay ahead:

“Standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realise that Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

It would take another three years of fighting before those with the power to end the conflict would talk half as much sense, or show nearly as much humility.